Music Theory Explained

(work in progress..)

I prefer music chord theory over sheet music. The difference is sheet music tells you exactly what to play and chord theory illuminates various pathways of acceptable routes. This allow the musician’s emotion to interpret the music in their own unique style. I feel that it gives more freedom to create something fresh, new, and original. The technical aspect of music composing will become a subconscious reflex that will direct focus to the attention of the development of the object’s personality that you are looking to serenade.

Table of Contents

- My Musical Background

- Chord Building

- Chord Progressions

My Musical Background

Music has always been a huge part of my life. Like everyone else, I started with the recorder flute. Shortly after, I picked up the viola and played that consistently for six years. I really love the sound that it produces.

As I got older, I started playing guitar but then shifted my focus toward the bass guitar. Bass and drums set the foundation of songs. Originally I started with sheet music, but as my musical knowledge increased, I started to notice many patterns in music and moved toward chord theory. Thats when I started playing the piano. For eight years piano was my favorite because its particularly useful when working with MIDI. Now the chromatic button style accordion is my favorite. The sophistication and intricacy of the inner-mechanics along with the incredibly intuitive button layout makes the accordion the most interesting instrument that I’ve seen so far.

What to Expect

What I’m going to explain in the upcoming entries, is the tonal relationship between two or more notes. The mood and feel of a song is created by the relationship between what note you just played compared to the note before it and the note your going to play after it. It’s quite easy to understand when you break it down to it’s simplest form. All a note is, is a sound frequency. Some frequencies blend better than others based on the mathematical relationship. Now your probably thinking, How many notes are there? Aren’t there a lot? Well what if I told you there were only 12 notes and everything else is just a repeat of the original twelve. Thats right, it doesn’t matter what instrument you play, you just need to understand the relationship between twelve notes and you can be off playing ANY style of music.

Chords

A chord is a combination of notes that harmonize together. When notes are played in certain combinations, they create more complex wavelengths. The interesting part about this, is that certain chords have the same wavelength of specific emotional vocal patterns. People subconsciously pick up on these and feel something they don’t understand. If I were to play a Dm6, it would invoke a sad emotion and if I were to play Cmaj, it would invoke a happy good feeling. That’s because those wavelengths mimic the tonal quality of those emotions.

There are only about 10 standard chords but in this lesson, we’re going to start with the basic four. Chords may look different from each other on the keyboard depending on where you started but if you count the keys from the root, you’ll find that every chord type is the same. What builds a chord is making sure all the required positions are played; It doesn’t really matter what order they’re played in. Someone could say there are over 100,000 chords if each one is inverted and rearranged in every combination through the frequency spectrum. Its the same chord but it’s qualities are pushed around.

Structure of a Chord

A basic chord is constructed of three main parts: Root, 3rd, and 5th. Think of the root as the foundation, its identity, as well as the name of the chord. Think of the 3rd as its right hand advisor, who’s really going to persuade how the root feels; whether that be happy, sad, uplifted, melancholy, or etc. And finally the 5th, which is the root’s opposite; the yin to the yang. The 5th can fill in empty space to make a chord more rich in harmonics. In more complex chords with numerous harmonics, the 5th is often dropped to keep the chord clean.

A basic chord is constructed of three main parts: Root, 3rd, and 5th. Think of the root as the foundation, its identity, as well as the name of the chord. Think of the 3rd as its right hand advisor, who’s really going to persuade how the root feels; whether that be happy, sad, uplifted, melancholy, or etc. And finally the 5th, which is the root’s opposite; the yin to the yang. The 5th can fill in empty space to make a chord more rich in harmonics. In more complex chords with numerous harmonics, the 5th is often dropped to keep the chord clean.

A chord starts on it’s root, labeled “R”. The Root is determined by which Roman Numeral you’re currently on in the Chord Progression. We are going to start from the root on Roman Numeral ‘I’ and use both the black & the white keys. Start on C, then label every black & white key in order until you reach eleven. Because note #12 should be C of the next repeating section as Roman Numeral ‘I’.

Now just hold down all the numbers associated with the chord, on the keyboard. And there you have it.

That leads us to our four main chords:

- R 4 7 – Major

- R 3 7 – Minor

- R 4 8 – Augmented

- R 3 6 – Diminished

Piano Chords

Major and Minor Chords

Major is your most common chord; It’s the bulk of the song, or main course of dinner. It has the feeling of being happy. Most songs, meaning over 90%, use this chord somewhere in their song. Does this mean a song can’t be written without it? No, but it’s uncommon to find any like that. The next most common chord is the minor chord. It has a feeling of sadness.

Major is your most common chord; It’s the bulk of the song, or main course of dinner. It has the feeling of being happy. Most songs, meaning over 90%, use this chord somewhere in their song. Does this mean a song can’t be written without it? No, but it’s uncommon to find any like that. The next most common chord is the minor chord. It has a feeling of sadness.

What makes these two chords different is determined by their 3rd. Now this is enough music knowledge to be off writing amazing songs, since most songs only ever use Major & Minor Chords. But what about the special chord that seem to bridge the gap?

Diminished and Augmented Chords

The next two chords, Augmented & Diminished, aren’t used as much as Major & Minor, but do show up quite occasionally. If you think of Major & Minor as Left & Right, think of Augmented & Diminished as Up & Down. Augmented being convex and Diminished being concave. These two chords are mainly determined by it’s 5th. If you listen and compare the two, you’ll find that the Aug feels open, free, & floating; while the Dim feels sinister & claustrophobic but these feeling are only when listened to in a vacuum. Diminished is used often as a leading hook between two major chords. It doesn’t sound sad/sinister at all; in fact it feels endearing and sincere as if taking a deep inhale ready to sing outward. Interesting huh?

The next two chords, Augmented & Diminished, aren’t used as much as Major & Minor, but do show up quite occasionally. If you think of Major & Minor as Left & Right, think of Augmented & Diminished as Up & Down. Augmented being convex and Diminished being concave. These two chords are mainly determined by it’s 5th. If you listen and compare the two, you’ll find that the Aug feels open, free, & floating; while the Dim feels sinister & claustrophobic but these feeling are only when listened to in a vacuum. Diminished is used often as a leading hook between two major chords. It doesn’t sound sad/sinister at all; in fact it feels endearing and sincere as if taking a deep inhale ready to sing outward. Interesting huh?

Practice those four chords. For more explanation with step by step instructional visuals, check out this page.

Diminished Chord Theory

What defines a diminished is a minor chord with a flatted fifth. Diminished chords are probably my favorite kind to play because they all carry a special link. The way they are set up creates these diminished bands. When you add a 7th to a diminished chord, you get four equidistant notes. If you play any three of the four notes, you will get a diminished chord of the same caliber. There are only three combinations, so there’s four chords to a band. There are twelve musical tones, so with a little math, we get three bands of four chords in total. Diminished chords are the only chords who’s math does this.

3 Diminished Chord Theory Bands

What does this mean?

Whenever you play a diminished chord, you can play every other chord or note within its band. Since all four chords within a band share the exact same notes, you can invert them in any way you want. This allows you to play a chord that has a slightly different feel while still remaining within the same key.

For example, if you are in the key of D minor, E diminished is in the scale. Instead of playing the E diminished, you can play G diminished or any other chord within it’s band to achieve a slightly different tone.

Switching bands creates a sinister feel and can be used to change keys dramatically. Its like a bridge is created for that moment where its acceptable to either switch to the new scale in a different key or stay put. Play this sound clip below for an example.

7th Chords

^Top

The chords below are the same as Major, Minor, Diminished, and Augmented, there’s just an extra note tacked onto the end of them. The extension note to these chords are called a 7th. There are 5 common types of seventh chords: Major 7th, Minor 7th, Dominant 7th, Diminished 7th, & Half-Diminished 7th. Seventh chords make any chord sound jazzy and sophisticated. They can be used to change the tonal qualities of a chord to shift and lead the music in a different direction. A seventh is exactly what it is called in a chord. You have your Root, your 3rd, your 5th, and now tacked on after, your 7th.

So where does this extra note go in said chord? Well that depends what kind of chord you are playing. Usually when playing a 7th, you don’t play the 5th. That’s because it makes the chord sound a little muddy from too many harmonics. To get around that, you can spread the chord out across the octaves but for right now we’re going to just remove the 5th. Later on I’ll explain how to spread chords out and how different spreads can change its motives.

Building a 7th Chord

The five most common seventh chords are:

- R 4 7 10 – Dominant 7th

- R 4 7 11 – Major 7th

- R 3 7 10 – Minor 7th

- R 3 6 10 – Half-Diminished 7th

- R 3 6 9 – Diminished 7th

Dominant 7th

A dominant seventh chord, or major-minor seventh chord, can often be seen labeled as: C7. This is your regular 7th Chord and will turn any chord into a jazzy sounding chord. It’s foundation is a Major chord build with a Minor on top. Whenever you play this chord, it makes the song want to move up a forth. (e.g. If your on C, you move to F; If your on A, you move to D.) If the chord sounds a little muddy, remove it’s 5th and play: R 4 10

A dominant seventh chord, or major-minor seventh chord, can often be seen labeled as: C7. This is your regular 7th Chord and will turn any chord into a jazzy sounding chord. It’s foundation is a Major chord build with a Minor on top. Whenever you play this chord, it makes the song want to move up a forth. (e.g. If your on C, you move to F; If your on A, you move to D.) If the chord sounds a little muddy, remove it’s 5th and play: R 4 10

Major 7th

A major seventh chord, or major-major seventh chord, can often be seen labeled as: CM7, CMaj7. This seventh chord has a very mellow sound and feel to it. It’s foundation is a Major chord build with a Major on top. If the chord sounds a little muddy, remove it’s 5th and play: R 4 11

A major seventh chord, or major-major seventh chord, can often be seen labeled as: CM7, CMaj7. This seventh chord has a very mellow sound and feel to it. It’s foundation is a Major chord build with a Major on top. If the chord sounds a little muddy, remove it’s 5th and play: R 4 11

Minor 7th

A minor seventh chord, or minor-minor seventh chord, can often be seen labeled as: Cm7. This seventh chord has a calming and nostalgic sound. It’s foundation is a Minor chord build with a Minor on top. If the chord sounds a little muddy, remove it’s 5th and play: R 3 10

A minor seventh chord, or minor-minor seventh chord, can often be seen labeled as: Cm7. This seventh chord has a calming and nostalgic sound. It’s foundation is a Minor chord build with a Minor on top. If the chord sounds a little muddy, remove it’s 5th and play: R 3 10

Half-Diminished 7th

A half-diminished seventh chord, or diminshed-minor seventh chord, or minor seventh flat five, can often be seen labeled as: Cø7, Cm7(♭5). It’s foundation is a Diminished chord build with a Minor on top. This chord is found quite often in Jazz music.

A half-diminished seventh chord, or diminshed-minor seventh chord, or minor seventh flat five, can often be seen labeled as: Cø7, Cm7(♭5). It’s foundation is a Diminished chord build with a Minor on top. This chord is found quite often in Jazz music.

9th Chords

^Top

A 9th Chord has it’s best results when used in small quantities. You can think of a Major 9th as of ‘something added’ where a Minor 9th as ‘something missing’. That ‘something’ being a sedimental feeling toward something. What kind of sedimental feeling is being dictated by whether its Major or Minor and the chords surrounding it.

Building a 9th Chord

- R 2 3 7 – Minor 9th

- R 2 4 7 – Major 9th

Minor 9th

When used with a Minor, it has a feeling of uncomfortable & uneasiness. It makes you want to lose the 9th as soon as possible and turn it back into a regular minor chord. The minor 9th is also considered a suspended 2nd. This is why it’s best in small quantities.

An example of this chord in use, is a HipHop Instrumental called, Borderline Evil, by Marc Zirin

Major 9th

When used with a Major, it almost gives a feeling of fulfillment. But can sometimes still give that feeling of uncomfortable & uneasiness.

Chord Progression

Fulfillment: F – G – A9

It’s almost like the notes in the chord progression stumble upon each other and come to a halt. It gives that sense of fulfillment.

6th Chords

^Top

6th Chords are very interesting because they add some color to the harmonics. They give your chord something different without pushing it’s limits while keeping the chord stable. These are great as a bridge and can create very diverse tones depending on it’s surrounding chords. Let’s start building our chords!

Building a 6th Chord

- R 4 7 9 – Major 6th

- R 3 7 9 – Minor 6th

Major 6th

These create a very colorful happy feeling. Its used to add some color and widen the pallet. It’s also great for smoothening transitions between chords, by having a stable chord with one more note in common with the next chord. If you actually look closer at a Major 6th, you’ll notice that it’s a Minor Seventh Chord in disguise. Because of this, it can easily be substituted. (e.g.: If your playing a C6, it could also be interpreted as Am; G6 can also be Em.) So basically a Major 6th is a Minor Seventh Chord.

Minor 6th

These are the mysterious sounding chord. When played, it creates a feeling of strangeness. It isn’t necessarily a bad feeling, it just feels different and like the sound is floating. These are best used as a dramatic pause. When you play them, drag them out and it will really grab the listener’s attention in anticipation for the next chords resolution.

An example of this chord in use, is a Cinematic Instrumental called, Party Cloudy, by Marc Zirin.

Chord Progressions

Dramatic Pause: D – Cm6

Smooth Transition: C – G6

Chord Progressions

Progression Theory

Now that you’ve learned the chords, we can begin on the very basic starting point of Music Chord Theory & Chord Progressions. Don’t worry, it’s easy as cake. This bit of theory will be explained on a piano, but can be applied to any instrument.

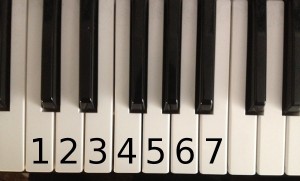

So as you’ve noticed, the piano has many white & black keys with repeating sections. And if you count them, there are 12 keys in-between each repeat. Thats 7 white keys & 5 black keys. I call this region The Main Playing Field. What determines what note you start on, is what key your playing in. In the picture here, The Main Playing Field starts on C, because we are in the key of C Major.

Chord Progressions

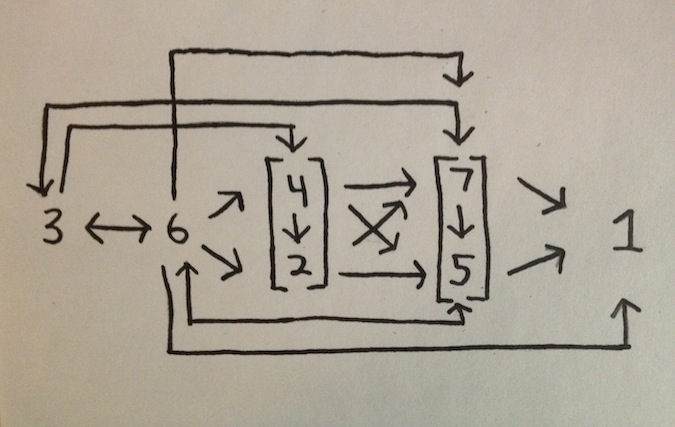

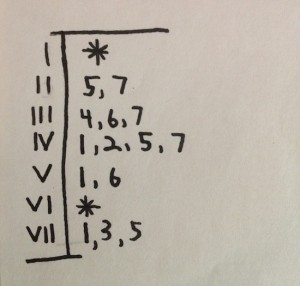

As seen in the picture, the white keys are numbered 1-7 starting on C. So that means that C = 1 , D = 2 , E = 3 , F = 4 , G = 5 , A = 6 , B = 7. We’re starting on C because is the easiest key to start off on. They are all on the white keys. Now if you can think of the Main Playing Field as numbers 1-7, consider this next image. About 85% or more of the music you hear anywhere follows a path on this chart. Dozens of songs following the same path. Ever wonder why so many songs sound similar to another? Creating a path using the arrows and rules almost guarantee a perfect sounding song.

Instruction Steps & Rules

- Start on #1.

- From #1, you may jump to any number.

- Now depending on what number your on, you must obey the direction of the arrows. The idea is to navigate your way back to #1.

- Now repeat the cycle and you have a song!

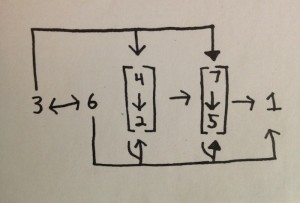

That is your Resolution; aka. a Cadence. A Cadence is the build-up of notes until you reach a peak, usually on either #5 or #7, to end back at the start on #1. Now what you just created is whats known as a Chord Progression; a series of chords or notes to create a tonal effect. You don’t always have to follow the arrows, but there needs to be a purpose in order to break the rules.

Use this chart on the right for a simpler view of the rules. The roman numerals in the left column tell you which numbers you can jump to next. The same rules apply. You start on number one and from there it’s a wild card. You can go to any number you want. After that, depending on which number you are on, you have to obey which numbers you are allowed to go to next. And the idea is to get back home at number one while following all the rules. Its exactly the same rules, its just a different way of looking at it.

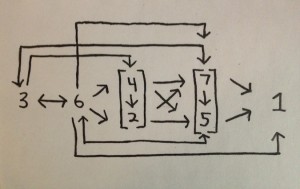

If you good at abstract symbols in diagrams and charts, here is an even simpler version of the chart; possibly too simple for a beginner. Now if this chart doesn’t make sense, then just ignore it and keep reading. It’s for people who want a simple clean chart with symbols to represent instead of all the extra lines. With the chart above, you can create your own symbols that make sense to you to signify direction. It’s less clutter. The arrows that are filled in dark (ones pointing at 7 & 5), mean that you can go back to the origin of the arrow. The little arm sticking out of the arrows (ones pointing at 2 & 5) means that it has a regular arrow pointing at the entire column (4 & 7 as well). I also wanted to point out the arrows between 3 & 6. It looks like you can go back and forth to each note indefinitely, which is partially true. You can do that and then depending on which notes you end on decides whether you pick the top path or bottom path.

As a refresher, you start on number one and from there it’s a wild card. You can go to any number you want. After that, depending on which number you’re on, you have to obey which numbers you are allowed to go to next. And the idea is to get back home at number one while following all the rules.

So if you take a closer look at the chart, you may have noticed that the only numbers that can approach #1 are numbers: 5, 6, & 7. These are your resolution numbers, also known as a Cadence. Now which one should you use, 5, 6, or 7? Well that depends on the effect your going for. The seven is the leading tone, meaning it creates a great flow and push into the next verse of the song. This is when a seven is resolved, or played, back to one. Five is more of a firm final resolution note. Playing a five before a one creates that feeling that its done and resolved. A five is the most powerful resolution because its the farthest away tonality wise. A seven is also a resolution note but not anywhere as powerful as a five.

So if you take a closer look at the chart, you may have noticed that the only numbers that can approach #1 are numbers: 5, 6, & 7. These are your resolution numbers, also known as a Cadence. Now which one should you use, 5, 6, or 7? Well that depends on the effect your going for. The seven is the leading tone, meaning it creates a great flow and push into the next verse of the song. This is when a seven is resolved, or played, back to one. Five is more of a firm final resolution note. Playing a five before a one creates that feeling that its done and resolved. A five is the most powerful resolution because its the farthest away tonality wise. A seven is also a resolution note but not anywhere as powerful as a five.

So why even bother resolving with a seven when a five is way more powerful? While a five is better than seven, do you really want to go straight to the end? Or do you tease at everything but what the ear wants to hear. You lay out some low value seven’s to create buildup and tension. Then when the moment is right, throw down the five to release all the tension and buildup.

Chord Progression:

(song above)

Medievil Kingdom

Key: A minor

1 – 3 – 4 – 5

A – C – D – A

Here are a couple common chord progressions to get you started in the right direction:

- 1 – 3 – 6 – 1

- 1 – 6 – 4 – 5

- 1 – 4 – 2 – 7

- 1 – 4 – 2 – 5

- 1 – 3 – 4 – 5

Now it takes a little practice and experimentation to figure it out. But when done correctly, you can compose some really dramatic & epic compositions. The best thing to do is practice, practice, & practice. You’re never going to get good at playing if you don’t play. It’s as simple as that. I learned everything I know about music from reading a few online articles, for basic structure, then banging on the keys of my piano and experimenting with what sounded good and what didn’t. Eventually you’ll start to notice patterns of what sounds good. Its like riding a bike, the muscle memory knows not to do something bad.

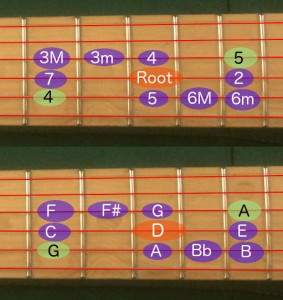

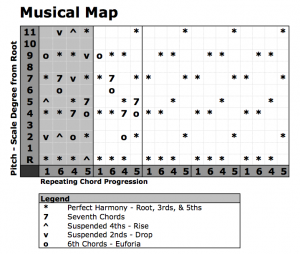

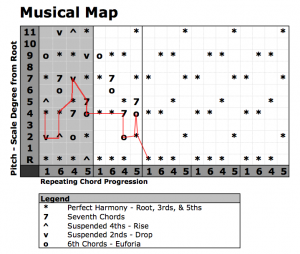

Musical Map

This chart shows all the different positions and how they transition to one another. Obviously this musical map has many paths and choices, so there isn’t any real right route. Which means it’s up to the composer which path they take. It can be short and sweet, or long, complicated, and adventurous. It’s up to you. All this map does, is tell where you are in relation to everything else and what’s coming up on the chord progression highway.

This chart shows all the different positions and how they transition to one another. Obviously this musical map has many paths and choices, so there isn’t any real right route. Which means it’s up to the composer which path they take. It can be short and sweet, or long, complicated, and adventurous. It’s up to you. All this map does, is tell where you are in relation to everything else and what’s coming up on the chord progression highway.

While it’s not hard to come up with a melody, I feel like this tool helps with the components & emotion of the melody. A strategically planned melody can appeal to a listener more when there is an emotional connection involved. Getting the right tones matched up with the correct emotion is specifically important, especially if your music is to sync up with a movie.

When playing a melody, there are many positions you can start from. Each starting point has a different feeling on the entire melody segment. While you can start anywhere, it’s best to start on a harmonizing note(unless its starting off with extreme tension); even better if the harmonizing notes are different. Usually the starting point is dictated by where you left off in the last melody segment.

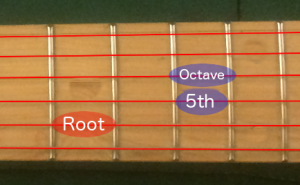

Root Position

If you start on the root, you get a standard neutral melody with nothing special. It’s a good starting point for the very beginning of a song because nothing is established yet. Something you can do is start from the 5th from the octave below. This creates a starter jump note to start the melody with a little propulsion.

3rd Position

Starting on the 3rd is a great place to start when you want to jump into the middle of the melody, like verse two. This is usually a fail safe starting point for any melody because it’s in the middle and its harmony is different from the root. From this point you can either increase the energy by moving up the spectrum, or decrease or maintain by moving down the spectrum.

5th Position

Starting from the 5th starts the melody off with power, conflict, and close to resolution. No matter whether you go up or down on the spectrum, it’s going to resolve. Just going up or down decides how it’s going to resolve, whether that be high or low energy, happy or sad, etc. etc.

How to Use the Map

Start at any position in the first column. Move as little or as much, just know that skipping too far at a time can sound chunky and disrupt the flow. Abide by the Key Signature’s Beats per Measure. When choosing your path, also know the Map Legend, so you know what kind of tone you’re going to encounter.

Start at any position in the first column. Move as little or as much, just know that skipping too far at a time can sound chunky and disrupt the flow. Abide by the Key Signature’s Beats per Measure. When choosing your path, also know the Map Legend, so you know what kind of tone you’re going to encounter.

The progression on the chart repeats over and over again and it’s exactly the same. I only added ALL the symbols on the first segments so the entire chart wasn’t cluttered.

The best way to become a great composer, is constantly explore new sounds and chord changes. Hearing a simple obscure chord change could be all it takes to write a huge multi-piece compilation.

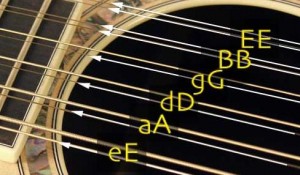

Guitar

The notes on the guitar are laid out in an interesting way. Throughout history the layout of the guitar notes have changed numerous times and there isn’t any correct way because the various tunings each serve a specific purpose. The standard tuning that everyone is familiar with provides the most chord possibilities. For acoustic guitar strumming, this is probably the tuning wanted. Every string is a perfect fourth higher than the last, except for between G and B, which is a minor third instead. Its really strange and more can be explained here.

However for electric guitar soloing, perhaps tuning each string to perfect fourths makes more sense. This method allows for quick identification of main positions in the progression. No matter where you are on the fretboard, this pattern is consistent and true. There are two ways to tune the guitar to perfect fourths. Raising the top E and B up half a step works but could put stress on the strings when bending the notes. Lowering the bottom E, A, D, and G down half a step and putting a capo on fret one worked the best for me.

Guitar solos are essentially fancy scales played quickly along a progression. When playing a solo, you want to express your creative freedom by playing all over the fretboard. If you haven’t learned all your scales yet, which I highly recommend you do, this method will show you all the notes that will harmonize with the note you are currently on.

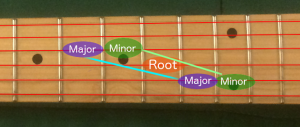

No matter which fret you are on, the fret directly above it will be its 4th. The fret directly below it will be it’s 5th. Up one string and one or two frets to the left, depending whether the scale is major or minor, is the 3rd. Down one string and one or two frets to the right, depending whether the scale is major or minor, is the 6th. Now don’t forget about the half step downshift between string G and B.

Now something interesting is if you turn this graph upside down, the shape is exactly the same. It’s almost as if major and minor are inverses of each other.

If you’ve ever played on a guitar, you’ve probably heard of a power chord before. It’s a cheap, simple, easy, and effective way to play harmonizing notes. They sound good but lack substance and intricacy. If you break a power chord down to individual notes, it contains a root, a 5th, and the same root one octave higher. Because it contains no 3rds, it can be played just about anywhere in any scale.

While a power chord contains just three notes, a full chord usually contains four to six notes, depending on where the chord is on the fretboard. A full chord usually contains two roots of different octaves, two 5ths of different octaves, and one or two 3rds.

Here are a few common chords on the guitar with each note and its classification:

A Major – A(Root) E(5th) A(Root) C#(3rd) E(5th)

C Major – C(Root) E(3rd) G(5th) C(Root) E(3rd)

D Major – D(Root) A(5th) D(Root) F#(3rd)

E Major – E(Root) B(5th) E(Root) G#(3rd) B(5th) E(Root)

F Major – F(Root) C(5th) F(Root) A(3rd) C(5th) F(Root)

G Major – G(Root) B(3rd) D(5th) G(Root) B(3rd) G(Root)

Playing the same note in a different octave gives a richer and fuller sound than just playing it in one octave alone. A great example of harmonizing octaves is the way a twelve string guitar is set up. Even though a twelve string guitar has twice as many strings of a standard, it’s not introducing any new notes. It not only contains all the basic strings of a standard guitar, but also pairs up with a second set of strings one octave higher. It’s very easy to play the pair together because they are so physically close to the basic ones that they are practically touching. When playing a full chord on a twelve string, your essentially playing four roots, four 5ths, and many 3rds. Your playing every note within the chord across the tonal spectrum in multiple octaves. It doesn’t get any more rich and full than that.

Playing the same note in a different octave gives a richer and fuller sound than just playing it in one octave alone. A great example of harmonizing octaves is the way a twelve string guitar is set up. Even though a twelve string guitar has twice as many strings of a standard, it’s not introducing any new notes. It not only contains all the basic strings of a standard guitar, but also pairs up with a second set of strings one octave higher. It’s very easy to play the pair together because they are so physically close to the basic ones that they are practically touching. When playing a full chord on a twelve string, your essentially playing four roots, four 5ths, and many 3rds. Your playing every note within the chord across the tonal spectrum in multiple octaves. It doesn’t get any more rich and full than that.